To Every Cow Belongs Her Calf

An early Irish Intellectual Property dispute

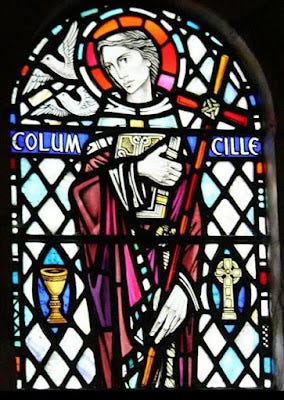

In Church Hill near St. Colmcille's well, abbey, and oratory you can visit St. Colmcille's birthplace. St. Colmcille is venerated at many sites in Donegal, whereas St. Patrick is more a northeastern and midlands saint, and Bridget is found in Kildare and the southeast.

According to Manus O’Donnell’s account of Colmcille's life, on the night before Colmcille was born Eithne saw a vision of a young man. The youth told Eithne that there was a flagstone in Lough Aikkbon which should be brought to Rath Cnó where the saint would be born. The stone was found by Eithne’s family and brought to this place. When Colmcille's was born, a cross-shaped niche opened up on the stone. She is also said to have produced a blood-coloured stone—an cloch ruadh—which was kept in Gartan and which had healing powers. (source)

The stone where Eithne labored is called Leac na Cumhaid, Stone of the Sorrows. The sorrow has nothing to do with Eithne. I've visited this place several times. A large flat stone faces the south, and behind it is a horseshoe-shaped cairn. Archeologists think these holes in the stone are a kind of rock art. They are always filled with water.

If Colmcille had not become a monk, he would have gone into his family business of early medieval politics. He was an O'Neill. It is my understanding that writing was the actual reason young Irish men converted to Christianity, not the asceticism and Jesus miracles. If you lived in a culture of oral storytelling, writing in 561 AD was as innovative as a punch card in 1961 AD.

For whatever the attractions, Colmcille converted to Christianity and used his family's money and influence to build abbeys, which were proto-universities teaching reading, writing, and book publishing. Abbeys competed with each other to attract scholars, each claiming to collect the rarest relics and holiest books. At some stage, he heard his former teacher Finnian had a St. Jerome’s Psalter. A psalter is a book of just the bible's psalms, which the monks used as prayers throughout the day.

Colmcille snuck into Finnian’s scriptorium and copied the psalter all in one night, in the light of a miracle candle he also happened to have. He returned his abbey and told everybody "Hey, come to my abbey, we have a St. Jerome's psalter too."

Finian accused Colmcille of stealing his book. Colmcille said “No, you have your book, I have my copy.”

Finian said, “That copy is mine too.”

“You luddite,” said Colmcille, “Information wants to be free.”

“You pirate,” said Finnian, “Information is precious, and you've robbed the feckin' Word o' God off me.”

They would have continued to assault each other with invective and verbiage, but Finian said, “Let’s ask the King to decide.” Colmcille agreed, because he knew he was right, and also because the king was his uncle.

King Diarmait wasn't quite sure what a book was, so Finnian handed him his original.

King Diarmait turned it over in his hands and stroked the fine old leather cover while Finnian made his case. “If someone is going to copy it, they need to ask me first, and make a donation.”

Then Colmcille handed his copy to the King, with its nice new leather cover. “Finnian’s single book could be burnt in fire or lost in a bog. Holy men like Finnian and me must spread God’s Words by copying. Copying is not theft.”

King Diarmait looked up from the book. “That's for me to decide, lad.”

”Yes, you’re right,” Colmcille obsequiously agreed. “And if copying were theft, it would not be as bad a crime as refusing to spread the word of God.” He flicked his eyes toward Finnian. “Like some people.”

King Diarmait couldn’t read, so from inside the frame-of-reference that was his world as a cattle baron, he understood that a book was a thing covered in a cow's skin. And so he formed his judgement: “To every cow belongs her calf, therefore to every book belongs its copy.”

As you might expect, losing history’s first intellectual property dispute due to illiteracy made Colmcille incandescent, and not in a holy way.

Colmcille went home and told his O’Neill relatives that King Diarmait basically called him a thief. The O’Neills attacked the King's clan, and before long 3,000 men died in a massive brawl near Sligo now known as The Battle of the Book.

Soon after, the war came home to Colmcille when he was right here at his birthplace, Gort na Leic, Field of the Flagstone.

A local man came up to him. “You arsehole, do you know how many of my friends and brothers died in your stupid Battle of the Book? I don’t even want live.”

Even though he knew he was right about copying the book, Colmcille felt responsible for the grief and loss of life. He knew envy was a sin as well as anybody. So he did what any miracle-working monk would do. He blessed the flagstone he was born on, and the water in its holes.

He gave the blessed water to the sad man, saying, “I didn't intend for all those guys to be killed in the war I started.” And for the rest of his life, Colmcille’s neighbor lived free of crippling sorrow, as does anyone who drinks of the water to this very day. (See photo below.)

Despite this miracle, Colmcille’s conscience caught up with him. He felt responsible that 3,000 pagan men had died fighting for his Christian vanity. He decided to leave Ireland, to build more more abbeys, and never rest until he had converted more souls than had been lost in the Battle of the Book.

He spent his last night in Ireland meditating on the Flagstone of Sorrows. He sailed the sort distance to Iona and started the monastery movement which spread Irish literacy across Europe and Saved Civilization.

Since the night Colmcille left, if someone sleeps here before they too leave Ireland, they will never be homesick.

And that is why this place is called Leac na Cumhaigh, "Stone of Sorrows."