Underground Ireland

"Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat."

Our village of Dunfanaghy faces Horn Head. Long ago, it was an island, but now it joins the mainland with a pretty bridge. I like to sit on the south-west dune and take in the view. I was attracted to this spot a while ago because of the white stones exposed through the dune. You can see them from Muckish.

Here Pippin and me looking back at Muckish and the Derryveaghs.

Long ago, people lived up here on Horn Head. We know this because their souterrain remains. A souterrain is a stone tunnel, under a dwelling, providing cold storage.

When archaeologists were last here, they knew there was a souterrain, but they couldn't find it.

Archeological Survey of County Donegal:

Class: SouterrainTownland: LURGABRACK

Description: A souterrain discovered here in 1968, and reported to NMI, consisted of a gently curving SW-NE passage at least 12m long. It was 1m high, 1.09m wide, the walls being constructed of stone and the roof of flags. There were two trap points consisting of projecting jambs and lintels 6.1m apart; it was located in a vast area of sand dunes. Unable to locate remains of souterrain at location marked on OS 6-inch map, hollow area located where souterrain is marked on the 6-inch map.

Eileen Battersby in the Irish Times:

Lacking the often romantic or eerie mythology and folklore of the ringfort, while also denied the dignity of burial sites, souterrains are perceived as merely underground structures, consisting of a passage, or passages, leading to one, or more, chambers. Archaeological research and speculation has seen them emerge as an intriguing combination of defensive measure and subtle housekeeping device - as a secure larder or cellar. Writing in 1789, William Beauford described the souterrain at Killshee, Co Kildare, as: "These caves, with others of a similar nature found in several parts of Ireland, were the granaries or magazines of the ancient inhabitants, in which they deposited their corn and provisions, and into which they also retreated in time of danger. ... As with any ancient monument, the individual site possesses an element of mystery. Yet the overwhelming sensation created by them is respect for the practicality that created them. Believed to have been constructed as places of refuge and - with the development of settlement and its greater food demands - storage, they are intriguingly unobtrusive. Excavations confirm such structures were never intended as formal burial sites and there have been very few instances where of human remains being found within. The scattered bones located from time to time are, therefore, most likely to have belonged to unfortunates who entered the souterrain in hope of safety."

Archaeologically they are associated with farm houses, most built during the Viking raids 800-900. Mythologically, they are associated with "Little People" who lived under the hills.

From the Schools’ Folklore Collection: A Fairy Souterrain

On Roddy's farm in the townland of Carva and Parish of Desertegney there is a fairy fort underneath the ground. It is supposed to have been constructed by the Danes, and afterwards to have become a home of the fairies. There is a large stone guarding the entrance, which however is now filled up.

Many years ago when it was open I counted seven rooms, and there is a passage running back for more than a quarter of a mile. The floor and roof are neatly flagged. Old people tell that in days gone by they many a time could hear the fairies dancing and singing inside this fort.

The story is also told that long ago at the full of the moon the fairies could be seen holding midnight revels and parades in the adjoining fields and on the banks of the stream which flows past.

The man who claims to have last seen these fairies is Neal McGrory of Sharagore. This was at six o'clock on a fine summer morning, when the fairies were playing games on the bridge of the Castleross stream near the fairy fort.

About fifteen years ago, someone found treasure inside the Horn Head souterrain.

A Hoard of Viking-Age Silver Ring-Money from Lurgabrack, Horn Head, Co. Donegal.

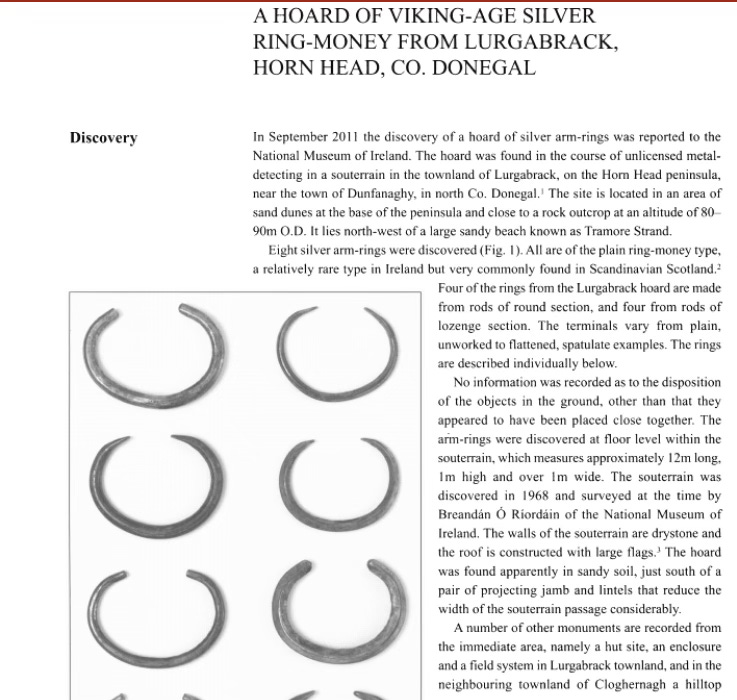

In September 2011 the discovery of a hoard of silver arm-rings was reported to the National Museum of Ireland. The hoard was found in the course of unlicensed metal-detecting in a souterrain in the downland of Lurgabrack, on the Horn head peninsula near the town of Dunfanaghy, in north Co. Donegal. The site is located in an area of sand dunes at the base of the peninsula and close to a rock outcrop at an altitude of 80-90m O.D. It lies north-west of a large sandy beach known as Tramore Strand.

Unfortunately, the find circumstances of this hoard did not allow for analysis of the disposition of the arm-rings and therefore it is not possible to speculate as to what type of container, if any, the objects were buried in.

One final quote from the archeology paper:

No information was recorded as to the disposition of the objects in the ground, other than that they appeared to have been placed close together.

And this is the tragedy of treasure hunters using metal detectors. Metal detecting is absolutely prohibited in Ireland, as any object under the ground on the island belongs to the Irish state. This is nothing like the law in the UK, where archeology "finds" belong to the landowner. They can keep what they find in their private collection, and if they want to sell, they must offer to museums first. British landowners split the proceeds of metal detecting with the finder.

The entrance to the Horn Head souterreign is hard to see, even if you know where to look.

Last summer I crawled through it after my friend revealed it to me.

Some souterrains are well known and often explored, and they sometimes gross and filled with trash and worse, and nice like this secret souterrain. Once past the entrance and the odd spider and slug, a souterrain can be cool and clean. It's just the right sized underground house for, say, a hobbit.